Copyright 2008

Mingmei Yip

Becoming a Writer

A Writer Grows Up in Hong Kong: Mingmei Yip's Story

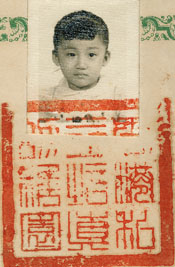

Mingmei in Kindergarden

Only after I was old enough to talk to my classmates did I realize how peculiar my family was. I was born to a scholar family; my father was a professional gambler with a degree in singing from the Beijing Military Defense Conservatory and my mother was an aspiring artist. When I was a child, my father always boasted to me how his uncle, a prominent General in China, won endless battles just by using his brain. He also told me how my cousins all had PhDs.

My grandmother from my mother’s side was the owner of the Pepsi Cola factory in Vietnam

before the liberation. Barely able to read, she took over the business after my grandfather

died suddenly of a stroke while in his early forties. My mother always boasted about

Grandma’s success and showed me pictures, now lost, of Grandma beside Joan Crawford,

then at the peak of her Hollywood stardom, and Wu Ting-

My grandmother came to visit us from time to time, but like so many old generation

Chinese women, she lavished attention on my brother but ignored me because I was

a girl -

Whatever my mother thought about this, she always had faith in my future. Once when on our way to a Chinese opera performance, I saw the crescent moon and blurted out: “Ma, look, the moon is like my clipped fingernail!” Amazed, Mother shot back: “Wah! Mingmei, you’ll be a writer someday!”

Me playing the Qin

Reminiscing

Sadly, after that evening I was not to see my mother again for eight long years.

Frustrated by father’s gambling away all her family jewelry, she set out for Saigon

to rejoin Grandma. My poor mother never knew anything of politics and arrived in

Vietnam when everyone else was struggling to leave – the communists were taking over.

The Pepsi plant was quickly nationalized and Mother placed in a prison camp as a

capitalist-

But my eight years of separation from my mother left me something. Out of my loneliness, I kept a journal in which I poured out my pain and fear but also my love and hope that my mother would come back to me. Now I know that this was my first training for my future career as a writer. Much later I learned to play the ancient Chinese musical instrument, the qin, and through this came to learn more about the lives of Chinese women, from aristocrats to courtesans, who had played it in the past.

Now both of my parents are, sadly, no longer in this life. If they are reading my

novel Peach Blossom Pavilion in their new incarnations, I hope they would be happy

to learn that their daughter has fulfilled their dream of becoming a scholar-

How I began to write

My name “Mingmei” in Chinese means “bright and beautiful;” these words are used to

describe fine weather, picturesque landscapes and pretty women. I like my name, which

was given by my mother who strongly believed the first day I was born that I would

grow up to be “ming” and “mei” -

I was born to a scholar’s family where my father was a professional gambler with a degree in singing (baritone) and my mother a teacher and an aspiring artist. When I was a child, my father always boasted to me how his uncle, a prominent General in China, won endless battles just by using his brain. He also told me how my cousins all had PhDs.

My father’s untiring boasting about our family inspired a childish vision in me.

So whenever grown-

One time when Mother took me out to an opera performance, on the way I saw the crescent moon and blurted out: “Ma, look, the moon is like my clipped fingernail!” Amazed, Mother shot back: “Wah! Mingmei, you’ll be a writer someday!”

Looking back, I realize that I was eight years old when I actually became a writer. It happened because my great aunt carelessly let my puppy Laili (“Bring Fortune”) run out of our house. When the puppy finally found his way home, he also brought with him a strange skin disease which would soon send him to his next incarnation. Angry and choked with sadness, I scribbled two letters, one to Laili, the other to my great aunt. The first began, “My dearest Laili…” and went on to express my wish that he would reincarnate as a baby girl so we could begin our next life together as sisters. The other began, “My most hateful Great Aunt,” and went on to accuse this strange woman who barely spoke to any of us.

Fearing that my parents might read the letters and scold me, I immediately slid them inside my schoolbag. When I awoke the next morning, however, I found Mother reading them. Unexpectedly, instead of being paralyzed by her angry eyes, I saw her lips lift almost to her ears. “Mingmei, you’re such a good writer. But,” Mother leaned to whisper into my ears, “don’t ever let Great Aunt see what you wrote!”

My desire to write, I believe, had started with the two letters, my mother’s praise, together with the stirrings of the small loves and hates my young heart was starting to experience in this dusty world.

As a child, I took little interest in talking and less in having friends. (My grandmother once asked my mother whether I was retarded!). I was happiest hiding myself beneath my father’s large office desk, thinking weird thoughts or dreaming strange dreams. In my mind, the moon would reach out to slap the sun. Or the dim sum on my plate would suddenly get up and tango.

At fourteen, my first article was published in a magazine. It was nothing special, but I was paid ten dollars for it. As soon as I got the big, fat check, I made the grand gesture of inviting a classmate to join me in devouring big bowls of steamy wonton soup with noodles, beef congee, and sizzling dim sum.

Later in college, I took as many courses as I was allowed. I particularly enjoyed two – Speech and Creative Writing. Our first assignment in Speech was to introduce ourselves to the whole class. That was when I found out that most people’s lives are pretty boring: May May had a mom, a dad, a little sister and every Sunday they all went out for buffet together. Meng Meng endured piano, ballet, and painting lessons every week to her mother’s great pride but her own suffering. And on and on.

Until my turn to give my speech, I decided that my voice would be a lion’s roar cutting right through this mundane buzzing. With a dramatic tone and an even more dramatic expression, I proclaimed that my mother was a workaholic and my father an alcoholic – what we would now call a dysfunctional family. At sixteen I ran away from home and lived with different boyfriends staying in filthy rooms at cheap hotels, even under the bridge in the park. After my speech, the whole class became uncharacteristically silent. Mrs. Wallacker, our bespectacled, deeply religious American teacher, was too upset to talk to me. She asked a girl student to comfort me and tell me to see her later. When I did, it was my turn to comfort her and then apologize by telling the truth that the story was, well, just a story. “Actually, it doesn’t really matter,” was her answer. A week later, I got an A for my speech.

I believe this event planted the seed of the fiction writer in me – not to lie in order to hide the truth, or to reveal it, but simply to tell a gripping story. Within an inspired narrative, I believe, something true is always embedded.

For creative writing class, each student would write a short story and the following

session, Miss Anderson, our petite brunette teacher, would pick the best to be read

aloud by a student to the whole class. In order not to stir up jealousy, the writer

would remain anonymous. Though I liked Miss Anderson’s liveliness and her pretty

green, jade-

Did she think that I was born mute?

One evening, I swore to the moon that my voice, be it strong or weak, whole or broken,

normal or perverse, would make a heaven-

So I started to draft my “masterpiece,” A dissection. It told about love, hate, jealousy and the search for truth – by describing the dissection of a beautiful, evil girl to see whether the color of her heart was truly black. To cut off her long tongue so she could no longer gossip nor slander (this in fact helped to dissipate her bad karma so she wouldn’t be reincarnated as a sewage rat nor be perpetually sawed in hell). To crack open her brain to see whether it was filled with garbage, vomit, or maggots. And so on, each act more gruesome than the previous one.

Voila! My story was given a loud voice, finally (read by a muscular boy with a booming voice but oddly feminine gestures). After the reading in class, boos and laughter and accusing fingers flew like saucers.

One boy yelled at his neighbor, “That’s you! Sadist!”

His neighbor pointed to a bespectacled nerd. “No, I love women. It’s him!”

The nerd wielded a finger at the muscular one. “Him! It’s him! That’s why he’s so excited. Sicko, reading his own sick joke!”

Finally, a Chinese Woody Allen stood up, looking through his thick glasses to scan all the other boys. “All right, which misogynist wrote this? Confess!”

All the girls looked stunned. I smirked inside.

A week later, Miss Anderson sent me a note: Mingmei, you write very well, but next time please give me something normal!

To be a good girl and be patted on the head had no appeal to me. I wanted to be a red dot among a vast expanse of green, a crane spreading its wings among a horde of hens.